|

|

|

| |

| |

|

| Holly Sidford |

BIO |

Transforming Community through the Arts

November 15, 2002

REMARKS |

“The National Funding Landscape for Art-based Places”

Remarks by Holly Sidford, Senior Associate, The Urban Institute |

| [Many thanks to Simeon Bruner, Emily Axelrod, Jim Stockard, Sally Young, and Jennifer Martin for putting this conference together. Also thanks to you, the participants today, not only for taking time to attend this gathering, but also for the work you do every day to make your community better places. |

| I lived in Cambridge for 15 years and consider New England my spiritual home, and my topic today – how to create and nurture art-based places – is one dear to my heart. So I am very happy to be here. But after Rick Lowe’s and Larry Goldman’s inspiring, and illustrated, stories this morning, I worry that my remarks today will strike you as very dry. Have some more dessert.] |

| I’ve been asked to speak about national funding landscape for art-based places. My comments are more impressionistic than scientific, because there is no funding field called “art based places;” no standard definition of terms; and no central repository of information. And although I was a grantmaker in the arts, parks and public places for many years, for past two years I have been focusing my energies on trying to understand the landscape of support for individual artists. My take on all this may be a little different than yours. So take my comments as reflections on a theme. I hope they might stir your thinking, and lead to further conversation. |

| In trying to put together some useful information for you today, I had to look in a lot of different funding pockets. The funding streams that support projects and organizations like yours include: |

cultural facilities

cultural planning

community arts

cultural tourism

visual arts

performing arts

parks and open spaces |

economic development

cultural districts

artists housing and live-work space

design arts

public art

historic preservation

youth development |

| And undoubtedly I overlooked some. |

| This means, in effect, there are lots of different potential sources of support. But it also means that it’s an ad hoc–ery. Every project, every place has to invent its own rationale, blend of partners, sequencing of investments, and long-term approach to sustainability. |

| So what can we make of the information from a these disparate sources? Here’s what I see as overall trends in funding that affects your work. I’ll start with the good news. |

What is the picture for private arts funders? Perhaps some of you don’t know that:

- 80% of private foundations in this country fund the arts. That number grows to 9 out of 10 for the largest foundations.

- Most private funders are local funders. This is particularly true in the arts, where there are only a handful of national or regionally significant private funders.

- In year 2000, funding for arts and culture reached $1.8 billion. This represents approximately 12% of all foundation giving. It represents an increase in absolute dollars, although down as a percent of total pie. Only education and human services receive larger portions of the total foundation giving.

- The total percent of foundation funding in the arts fluctuates a bit from year to year, but has remained fairly steady over the past decade. It’s on a par with foundation giving to health.

- Portions for community arts, historic preservation, visual arts and architecture are rising, but giving to performing arts and museums still tops the charts — 32% and 29% respectively.

- Capital projects receive healthy support – 32% of all arts giving in the year 2000. Only in science and technology is a larger percent of funding directed to capital projects.

- And a 1999 Foundation Center survey of trends and attitudes among arts funders revealed some interesting information:

- Arts funders nation-wide are anxious about the marginalization of arts, and the lack of an integrated role for the arts in society and civic life;

- Many foundations are funding more community-oriented programs; and

- Many are funding longer-term (that is, not just one-time or one-year grants), and are increasingly open to partnerships.

- This is good news because it suggests movement in your direction.

|

What about public sources at the federal, state and local level?

- While the National Endowment for the Arts is still limping, there has been growth in the line items in federal budget directed to arts-based projects, many of which are capital projects.

- There is growing recognition of usefulness of culture-based economic development among state and local government sources. For example,

- The National Governors Association (NGA) and US Conference of Mayors have held numerous sessions on cultural districts and arts-based economic development.

- Phil Psilo, Director of Economic Growth and Technology Policy at the NGA, put it this way recently:

“There is an understanding now that you must have an ability to build a cultural component into development to retain talented and mobile workers. Culture is the key to economic development now. Look at any trend analysis and data. Investment follows human capital. And human capital, to a surprising extent, follows the arts.”

- This may explain some of the phenomenal popularity of Richard Florida’s new book, The Rise of the Creative Class, which discusses the importance of creative workers – knowledge workers, technology workers, artists, designers, and others – to healthy communities. Florida is getting rich giving speeches and consulting to governors, mayors and local political leaders in communities across the land. He has irritated a lot of people with his notions about class, but his ideas about the importance of creativity and the arts to urban American are getting a broad hearing.

- And let me draw your attention to a newly-issued report from Center for Urban Future, published earlier this week. This report, “The Creative Engine: How Arts and Culture is Fueling Economic Growth in New York City Neighborhoods,” abounds with interesting (and adaptable) examples of innovations that link culture and economic development, not just in New York City but also places such as Portland, Oregon and Philadelphia

|

My survey of resources also showed:

- Growing numbers of local initiatives promoting cultural initiatives, including:

- Hotel/motel taxes designated for the arts;

- A variety of other tax breaks and tax incentives aimed to boost the arts and culture;

- More than 90 cultural districts in cities across the country;

- A growing number of public sector artists’ live-work space initiatives, such as the one the Boston Redevelopment Authority has spawned right here;

- And many inventive (and often unintended) local uses of federal investments, such as allocating ISTEA money to support public art, and Empowerment Zone funds to finance cultural facilities.

- And a wide variety of municipal agencies, not just local arts councils, are now supporting the arts.

- A new report by Ohio State University, Local and National Profiles of Cultural Support, shows that a surprising array of local public agencies are supporting arts projects and cultural spaces, including:

- Parks, public works, transportation, community planning, youth services and others.

- Many of these agencies are funding programming, but some are financing capital and infrastructure projects. And, as Rick Lowe’s and Larry Goldman’s remarks showed, the reciprocal relationship between programming and capital funds is undeniable.

- I think this expansion of local, non-arts agencies funding the arts may be the real growth area of the past ten years. But no one has enumerated the commitment, so we don’t yet know its monetary value.

|

And what can we say about the commercial sector?

- There is lots of evidence that the commercial sector sees cultural investments as good business.

- Big projects, like the New Jersey Performing Arts Center or Playhouse Square in Cleveland, have become organizing ideas for local corporate communities, and have also spurred inventive private-public partnerships.

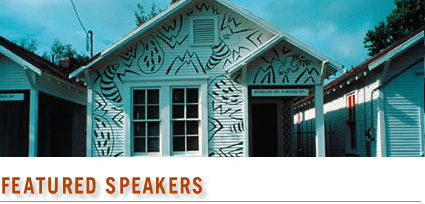

- The same is true, if on a lesser scale, for smaller projects like Project Row Houses or the Village of Arts and Humanities in Philadelphia or Dudley Square here in Boston. These initiatives have become organizing vehicles for smaller-scale businesses and local property owners.

- Another interesting development can be seen in the business sector’s application of the idea of economic clusters to arts and culture. Initiatives such as the Creative Economy Initiative of the New England (Business) Council and Portland, Oregon’s Creative Services Industry Initiative demonstrate that, for the purposes of economic and workforce development, the business sector is beginning to make useful connections between the commercial and nonprofit creative sectors. While nascent, these initiatives are very interesting, and likely to grow in number.

|

| Let me return to Richard Florida for a minute, and to the work we have been doing at the Urban Institute on artists, because Florida’s work and ours draw attention to a fourth, “hidden” sector of support for art-based places: the creative workers in every community. |

Florida asserts that:

- 30% of the work force is now composed of “creatives” – knowledge workers, technology specialists, designers, artists, etc.

- These creative workers are increasingly important to the health and vitality of cities. You want to have these people in your town because – unlike 20 years ago when workers had to move to places where they could find jobs – now businesses are more likely to re-locate to be near concentrations of creative workers.

- What do these “creatives” want from the places they live? Among other things,

- They want creative stimulus.

- They want places, “scenes,” where there is a good mix of commercial and nonprofit arts activity.

- They want opportunities to participate in the arts (and in other endeavors, including outdoor sports activities).

- And they want diversity, and opportunities to intersect with people of different kinds.

|

Florida recognizes artists as a critical component of the creative sector. And our research at the Urban Institute backs this up. From our study, we know:\

- There are 2+ million professional artists nationwide (and this is probably a significant undercount, because there are many people who are master craftsmen and artists in different fields but who make their living outside the arts, and therefore don’t count themselves as professional artists on their IRS forms).

- There are another 30 million people who pursue the arts as serious amateurs, actively engaged in the making works of art and honing their skills in their chosen field.

- Artists are catalysts who help other people take their creativity seriously. This is especially true at the neighborhood level where artists in all disciplines show expanding interest in public service and community engagement.

- And some artists are natural placemakers. We have a few in the room with us today. Rick Lowe, Mike Blockstein, Umberto Crenca, Susan Rodgerson.

- Talented artists live in every community and too many go untapped as resources for making art-based places. Local artists and creative workers are an important asset to your work.

|

| So there are many positive indicators and opportunities. What about the challenges? I’ll return to my three primary sectors. |

Private arts funders, for the most part, are

- Still focused on institutions, and most on larger institutions such as museums, symphonies, performing arts facilities and operas.

- Their grants are relatively small (65% of all arts grants are in the $10-25,000 range).

- In fact, 96% of arts grants are under $500,000; but interestingly, the top 4% represent more than half of total dollars awarded.

- These numbers, I’m sure, confirm your experience. The foundation funding landscape is dotted with many, many small grants, and just enough very large grants thrown in to make wonder what you are doing wrong.

- Among arts funders, almost none are thinking about comprehensive community cultural development or linking their private investments to city-wide or regional strategies. I suspect this confirms your experience too.

- And finally, foundation portfolios hit badly by the economic downturn. And for most foundations, the arts are not the highest priority and they are making disproportionate cuts here.

|

And the public sources?

- As I said, the Endowment is very wounded. In my view, the loss of the NEA’s leadership and vision – and the use of its bully pulpit for new thinking – is as important as its loss of money.

- Economic constraints are being felt in all parts of government, and especially state and local levels. This restricts movement and agencies’ receptivity to new ventures.

- And it’s still an ad hoc situation; there is no “discipline,” training or network to support innovations by the public sector in this area.

|

These conditions hold true for the commercial sector as well.

- Economic constraints are real.

- Work in this area still depends tremendously on the interest and drive of individual business leaders.

- And for business, too, it’s still an ad hoc situation; no standard, training or network exists to support innovations.

|

So the bottom line is:

- You are not going to get most of your money from arts funders.

- Nor are your most successful arguments for funding going to be about the intrinsic value of art.

- You’re going to have to be inventive, connective, democratic, and participatory.

- And you’re going to have to make it up as you go.

|

| In such a highly competitive funding environment, what advantages to you have in seeking money for art-based places? The four projects we’re showcasing today illustrate some of the aspects of this kind of work that have appeal to funders in many sectors. |

| These projects share a set of common characteristics, of which I think five are most important.

1. They have values grounded in community service and participation; and they’re connected to community drivers.

By community drivers, I mean generally-held social priorities and motivators, including obvious ones such as economic development, youth development, community revitalization and jobs; but also less obvious ones such as racial and class tolerance and boundary-crossing, community history, environmental protection, and building community’s sense of efficacy.

2. They have inspiring, multi-faceted visions.

I think of them as having triangular vision, because they have vision for three important targets: for art, for artists, and for the community. Further, in these projects, that triangle is equilateral, offering equal value or importance to the art, the artists, and the community. And these projects, artists are taken seriously, given real work, asked to help the community make meaning for itself and others. The importance of this attitude can’t be underestimated; it has strong impact on success.

3. These projects all have sustained, tenacious leadership – what Betsy Barlow Rogers, the visionary founder of the Central Park Conservatory, calls “passion, patience and persistence.”

4. They have excellent designs.

They are beautiful, inspiring places. They have clear, over-riding identities combined with elements of surprise. They attract diverse people with a mix of continuous activity and a sense of safety and comfort. They have affirmative relationships with neighboring spaces. And they are living bridges to both local history and the global world we inhabit.

5. And last, but not least, their leaders are willing to learn other languages and create multiple partnerships to achieve their vision.

I’m sure when Rick Lowe was studying painting with John Biggers, he had no idea he would be talking about real estate values, foreclosures and marginal interest rates ten years later. And Larry Goildman did not start his career hoping to become an expert on parking garages. But they – and the leaders of other successful art-based places – realized they had to learn the languages of real estate, finance, community development, education and other fields if they were to reach their goals. And in learning these new languages, they’ve made hundreds of new allies for the arts.

|

| These qualities are stand out characteristics for funders in all sectors. These qualities are your strategic advantage. |

But the fact is, there aren’t enough resources for this kind of work and the sources that do exist are disconnected. To make a real jump in available resources for this field, we concerted collected effort to raise the visibility and credibility of our work.

- We need a national, maybe international, database of successful arts-based places. And we need much better information – strategically collected and used – on the impact of artists and community-based institutions on communities. This includes economic impacts (on local business, real estate values); social impacts (tolerance, truancy, boundary-crossing, and neighborhood stability); political impacts (voting rates and political engagement); and environmental impacts, among others.

- We need a fuller understanding of the public policies that facilitate (and hinder) culture-based economic development. What do all these recent studies and initiatives tell us about which progressive public policies ought to be replicated more widely?

- We need more and more energetic local, regional and national networks, facilitated by conferences such as this one, as well as publications, listservs, hotlines, etc.

- We need spokesmen for this work from the business and government sectors.

- We need various graduate schools – not just in the arts, architecture and design, but also in business, community planning, public health and other sectors – to recognize the value of this inter-disciplinary work, and teach it to the next generation.

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|